Interior on Central Park West

New York, NY

1987–88

This project undermines the stability of basic architectural concepts through a strategy that places modernism in the context of history, rather than in the immediate moment. The process of designing the project offers the inspection of meaning rather than the specious clarity of a manifesto.

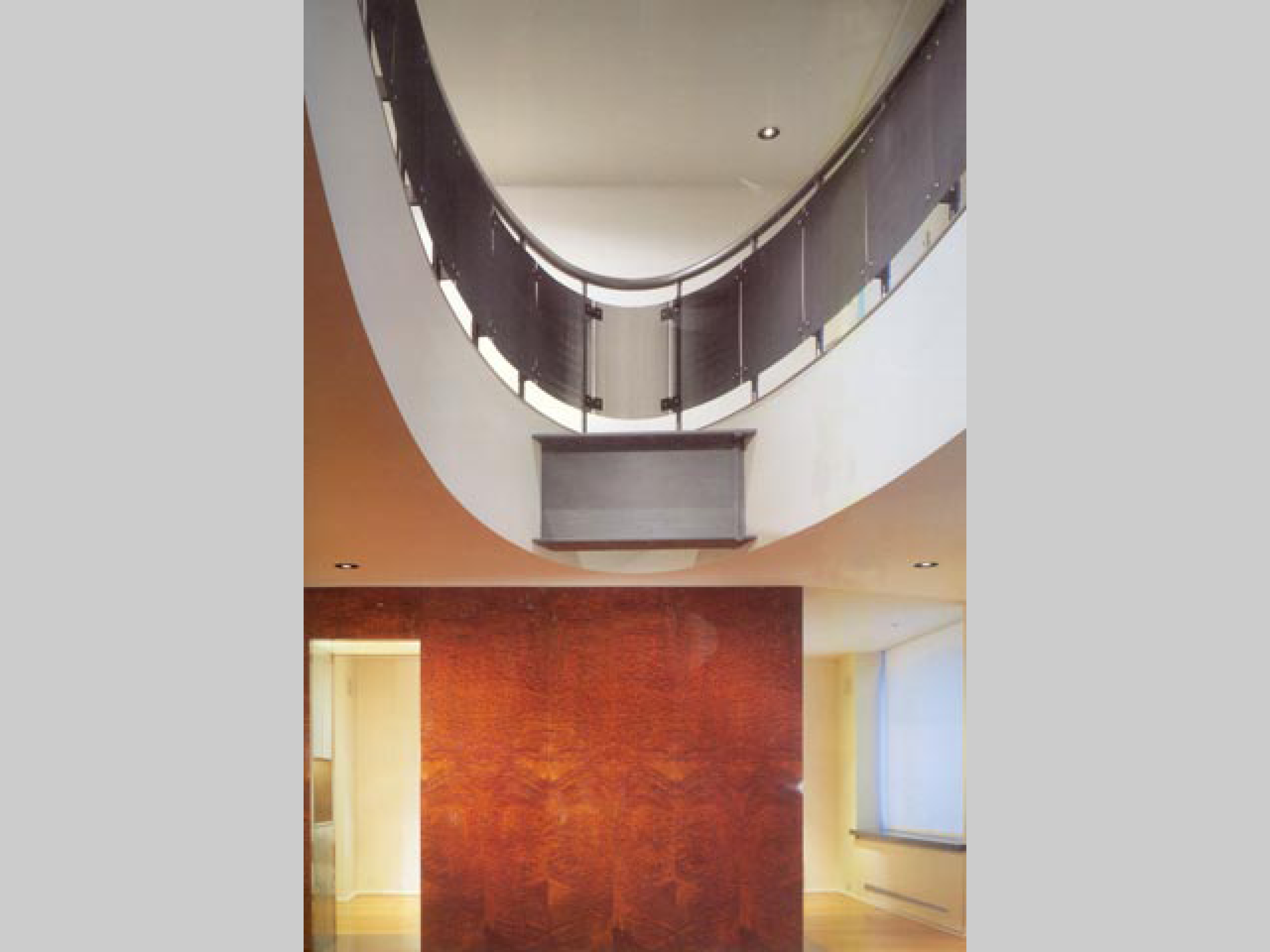

The first floor plan includes movement. The pinwheel formal organization of the walls is reiterated by a curved stair implying a spiraling. The pinwheel plan produces an alternating reading: on the one hand, it appears as a figure in a neutral modern space, and on the other, it organizes volumes separating rooms that read as figures. This fluctuation of readings produces rooms coexistent with the spatial flow of the free plan.

The blurring of oppositions is carried through to detailing, where luxury and austerity are the alternating readings. The apartment works within the constraints of use, while at the same time it subverts the traditional notion of opulence, even as a modernist like Mies van der Rohe understood it. The quality of the materials and the level of detailing breaks down the separation between furniture and architecture.

Classicism is often an applied system of ornament that is a visual, representational structure rather than a ‘true’ expression of structure or materials. The classic approach to detailing is exemplified by the molding, which conceals a joint between materials. In the modernist approach, a joint is treated as a separation, a reveal, allowing each material an independent expression of its own nature. Neither approach is used in this apartment; instead, materials butt each other. An aspect of modern detailing is retained, in that real materials—steel and wood—retain their own expression. But there is also the aspect of concealment; complex sleight-of-hand detailing is used to achieve the desired effect.

Second Door—The door to the powder room is an abstract, steel plane affixed to the wall.

Third Door—The curved door to the kitchen literally disappears as an element of the wall.

Fourth Door—The round, steel, sliding door to the pantry is conceived as a montage of a steel safe door, running on off-the-shelf library ladder hardware, with a commercial refrigerator door handle.

Fifth Door—The winged, wood and steel door to the master bedroom hangs on a double-height steel flagpole.

Sixth Door—The bar is a deep door.

Seventh Door—The two doors flanking the fireplace are defined by two vertical steel plates; a fragmented, alabaster lintel floats above.

Eighth Door—All other doors are ‘drawings’ on the walls. The frames disappear and the doors become outlines.

Historically doors are conceptualized in different ways, from doors that are treated as frames to heighten the qualities of separation and passage, to doors that are played down or made to disappear in order to emphasize continuity of space and freedom of movement. The doors in this apartment oppose these two strategies and add a third. The entry door for example, is steel with a massive, steel frame. In contrast, the portals cut in the fireplace wall between the living and dining rooms are treated as punched openings through the thick wood plane. The waist-high steel plates on either side of the door are flush against the wood wall, as if they were leaning against it, and the alabaster lintel above it, treated as a floating plane that is almost dematerialized, emphasize the articulation of openings from the front view of the city. The door of the powder room, a steel plane “over” the wall, represents a third type.

Doors acquire meaning within a system of differences. As objects, they acquire characteristics that take them away from their specificity. As spaces, they are either semantically charged, as in the case of the bar, or syntactically placed in the overall sequence of spaces, as in the dining/living room doors.

The first floor plan includes movement. The pinwheel formal organization of the walls is reiterated by a curved stair implying a spiraling. The pinwheel plan produces an alternating reading: on the one hand, it appears as a figure in a neutral modern space, and on the other, it organizes volumes separating rooms that read as figures. This fluctuation of readings produces rooms coexistent with the spatial flow of the free plan.

The blurring of oppositions is carried through to detailing, where luxury and austerity are the alternating readings. The apartment works within the constraints of use, while at the same time it subverts the traditional notion of opulence, even as a modernist like Mies van der Rohe understood it. The quality of the materials and the level of detailing breaks down the separation between furniture and architecture.

Classicism is often an applied system of ornament that is a visual, representational structure rather than a ‘true’ expression of structure or materials. The classic approach to detailing is exemplified by the molding, which conceals a joint between materials. In the modernist approach, a joint is treated as a separation, a reveal, allowing each material an independent expression of its own nature. Neither approach is used in this apartment; instead, materials butt each other. An aspect of modern detailing is retained, in that real materials—steel and wood—retain their own expression. But there is also the aspect of concealment; complex sleight-of-hand detailing is used to achieve the desired effect.

(read more)

Doors

First Door—The entry door is a figural, massive, steel door and frame, quoting Adolf Loos.Second Door—The door to the powder room is an abstract, steel plane affixed to the wall.

Third Door—The curved door to the kitchen literally disappears as an element of the wall.

Fourth Door—The round, steel, sliding door to the pantry is conceived as a montage of a steel safe door, running on off-the-shelf library ladder hardware, with a commercial refrigerator door handle.

Fifth Door—The winged, wood and steel door to the master bedroom hangs on a double-height steel flagpole.

Sixth Door—The bar is a deep door.

Seventh Door—The two doors flanking the fireplace are defined by two vertical steel plates; a fragmented, alabaster lintel floats above.

Eighth Door—All other doors are ‘drawings’ on the walls. The frames disappear and the doors become outlines.

Historically doors are conceptualized in different ways, from doors that are treated as frames to heighten the qualities of separation and passage, to doors that are played down or made to disappear in order to emphasize continuity of space and freedom of movement. The doors in this apartment oppose these two strategies and add a third. The entry door for example, is steel with a massive, steel frame. In contrast, the portals cut in the fireplace wall between the living and dining rooms are treated as punched openings through the thick wood plane. The waist-high steel plates on either side of the door are flush against the wood wall, as if they were leaning against it, and the alabaster lintel above it, treated as a floating plane that is almost dematerialized, emphasize the articulation of openings from the front view of the city. The door of the powder room, a steel plane “over” the wall, represents a third type.

Doors acquire meaning within a system of differences. As objects, they acquire characteristics that take them away from their specificity. As spaces, they are either semantically charged, as in the case of the bar, or syntactically placed in the overall sequence of spaces, as in the dining/living room doors.