A Critical Reading of the Urban Text—Les Halles

Paris, France

1980

Gandelsonas

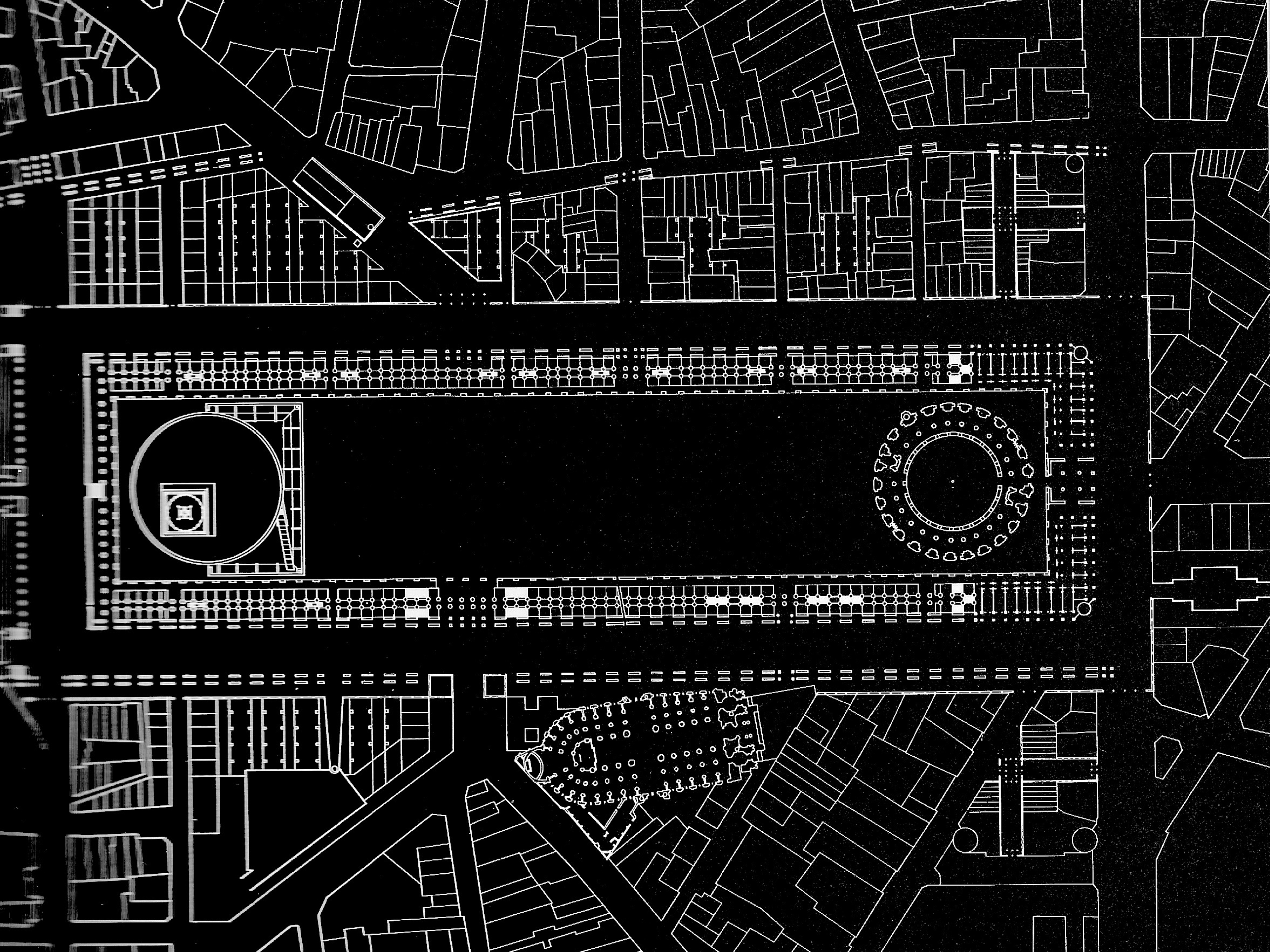

Throughout history the Les Halles quarter of Paris has undergone continuous morphological transformations as a result of the successive construction of public buildings. This project proposes a different kind of transformation instituted through the construction, not of another public building, but of a public place. This change will displace buildings, which now occupy a privileged, prioritized position, in favor of the ensemble by which they are articulated. Buildings will function as boundaries of the enclosure of public spaces, as elements of transition between one space and another.

The two spaces proposed by this project take shape around a building-wall that defines and separates them. This four-sided building-wall, formed from existent and newly developed buildings, circumscribes a rectangular plaza and defines an adjacent, ring-shaped street. The street, in turn, separates the building-wall from the urban fabric, appropriates its contiguous edge as its external limit, and makes it into an urban wall. The interior, the building-wall, acts as an opaque, impermeable block, and confines a concentrated space, which can be perceived as a totality. The exterior, the urban wall, acts as a filter, permeable to the urban forces that distort and deform it, and defines a diffused, linear space, which can only be perceived sequentially. As the degree of resistance to the forces of the city is thus increased from the exterior to the interior walls, the stability of the space is also increased.

Finally, the innermost wall, the interior side of the building-wall that faces the plaza, defines the architectural qualities of this public space. This wall, planned to exceed the medium height of the other buildings of the quarter, emphasizes its own verticality. It is incised by windows that open out to the sky and by doors placed on the axis of the destroyed pavilions by Louis-Pierre Baltard. The wall splits at the intersection of the prolonged axis of the lateral door of the St. Eustache Church.

The project also proposes to intervene in the closed dialogue that now exists between the Bourse and the St. Eustache Church. As the Bourse is transformed, to accord with the elongated proportions of the interior public space, its relationship with the church can no longer be sustained. It becomes necessary to introduce a new monumental element, a third term, into this relationship. A tower modeled on the lighthouse in Jean-Nicolas-Louis Durand’s nineteenth-century treatise is proposed. This shift initiates a new dialogue, which opens onto the register of the civic, between the Bourse and the tower, and displaces the church outside.

Through the dynamism of its proportions (one unit in width to five in length) and the convex limits of its monuments, the space enclosed by the interior wall, containing the Bourse and the tower, proposes a transformation of the typology of the Place Royales.

The urban wall that surrounds this space is composed of existent urban blocks and newly developed blocks of the same typology. The wall has two opposing definitions—solid building-wall and open ring-shaped street. The two sides of this wall segment repeat Baltard’s original design for the facade of the Les Halles pavilion: the side that faces outward, toward the city, reproduces the brick base of the design; the side that faces inward, toward the interior spaces and delimits the ring-shaped street, reproduces the cast iron superstructure. Once again there is a grading of the permeability of the wall surfaces and an increase in the force of resistance from the exterior to the interior. Similarly, as the converse placing of the two parts of the design resists the possibility of a totalized perception, the dispersal of space by a routing temporality is also increased at the exterior edges.

The corners of the urban wall are defined by four public spaces. The west, north, and south sides are marked by two cross-shaped commercial galleries carved out of the existing urban block. The eastern side is marked by two squares; the existing monument in the south-eastern square is transposed to the newly developed northeastern square, leaving a void as a mark of the south-east corner. Their four corners act as knots, by which the proposed space becomes stitched into the surrounding space of the city.

In addition, four crucial gates open the urban wall, by operating as points of ingress and egress between the spaces of the proposed project and those of the city. The western wall opens toward the Louvre, the northern wall toward the church and the markets, and the eastern, double-gated wall, pierced through by a window as well as a door, toward the new International Hotel and the Beaubourg center. The project, then, a construction of spaces, sets out its own spacing, releases its claim to autonomy, and becomes an interval along the urban passage.

The two spaces proposed by this project take shape around a building-wall that defines and separates them. This four-sided building-wall, formed from existent and newly developed buildings, circumscribes a rectangular plaza and defines an adjacent, ring-shaped street. The street, in turn, separates the building-wall from the urban fabric, appropriates its contiguous edge as its external limit, and makes it into an urban wall. The interior, the building-wall, acts as an opaque, impermeable block, and confines a concentrated space, which can be perceived as a totality. The exterior, the urban wall, acts as a filter, permeable to the urban forces that distort and deform it, and defines a diffused, linear space, which can only be perceived sequentially. As the degree of resistance to the forces of the city is thus increased from the exterior to the interior walls, the stability of the space is also increased.

Finally, the innermost wall, the interior side of the building-wall that faces the plaza, defines the architectural qualities of this public space. This wall, planned to exceed the medium height of the other buildings of the quarter, emphasizes its own verticality. It is incised by windows that open out to the sky and by doors placed on the axis of the destroyed pavilions by Louis-Pierre Baltard. The wall splits at the intersection of the prolonged axis of the lateral door of the St. Eustache Church.

The project also proposes to intervene in the closed dialogue that now exists between the Bourse and the St. Eustache Church. As the Bourse is transformed, to accord with the elongated proportions of the interior public space, its relationship with the church can no longer be sustained. It becomes necessary to introduce a new monumental element, a third term, into this relationship. A tower modeled on the lighthouse in Jean-Nicolas-Louis Durand’s nineteenth-century treatise is proposed. This shift initiates a new dialogue, which opens onto the register of the civic, between the Bourse and the tower, and displaces the church outside.

Through the dynamism of its proportions (one unit in width to five in length) and the convex limits of its monuments, the space enclosed by the interior wall, containing the Bourse and the tower, proposes a transformation of the typology of the Place Royales.

The urban wall that surrounds this space is composed of existent urban blocks and newly developed blocks of the same typology. The wall has two opposing definitions—solid building-wall and open ring-shaped street. The two sides of this wall segment repeat Baltard’s original design for the facade of the Les Halles pavilion: the side that faces outward, toward the city, reproduces the brick base of the design; the side that faces inward, toward the interior spaces and delimits the ring-shaped street, reproduces the cast iron superstructure. Once again there is a grading of the permeability of the wall surfaces and an increase in the force of resistance from the exterior to the interior. Similarly, as the converse placing of the two parts of the design resists the possibility of a totalized perception, the dispersal of space by a routing temporality is also increased at the exterior edges.

The corners of the urban wall are defined by four public spaces. The west, north, and south sides are marked by two cross-shaped commercial galleries carved out of the existing urban block. The eastern side is marked by two squares; the existing monument in the south-eastern square is transposed to the newly developed northeastern square, leaving a void as a mark of the south-east corner. Their four corners act as knots, by which the proposed space becomes stitched into the surrounding space of the city.

In addition, four crucial gates open the urban wall, by operating as points of ingress and egress between the spaces of the proposed project and those of the city. The western wall opens toward the Louvre, the northern wall toward the church and the markets, and the eastern, double-gated wall, pierced through by a window as well as a door, toward the new International Hotel and the Beaubourg center. The project, then, a construction of spaces, sets out its own spacing, releases its claim to autonomy, and becomes an interval along the urban passage.