Design as Reading

Roosevelt Island, New York, NY

1975

Gandelsonas

We decided instead that the competition ought to be treated as material for considering a series of questions concerning the housing problem. In this regard, our project should be understood as part of the more general work of reflection on architectural ideology, that is, on the problem of the production of sense in building design and construction.

(read more)

The City

Architectural ideology needs to be displaced toward a new definition in which notions of design and reading, as operations of production and transformation of the meaning of the constructed world, play a fundamental role. In our proposal the displacement is effected by the introduction of formal repositories and operations derived from the architectural urban configurations—that is to say, the architecture of a production not completely controlled by architectural codes but rather subject to extra-architectural determinants, to ‘other’ logic systems governing production of meaning in design. In design as well as in reading, meaning is derived from a chain of fragments rather than from a content adhering to a form.(read more)

The Operations of Design

In design, the operations are closer to transcription, juxtaposition, and transformation than to invention.Transcription deals with existing typologies. Examples of this operation are apparent in the variation of facades on Main Street (which transcribe the variation of facades in the city), the town houses, the waterfront, the towers, the setback, etc. Examples are also evident in the transcription of architectonic fragments such as Mies van der Rohe’s curtain wall or Le Corbusier’s fenetre en longueur.

Juxtaposition appears out of a logic in which fragments act as neutral elements in contraposition to the articulations that come to play a principal role. In this sense, and in terms of the articulation between fragments, public places occupy a fundamental role. Public places weave through and are continually blended with the dwellings, as in the stoops of town houses, streets, belvederes, etc.

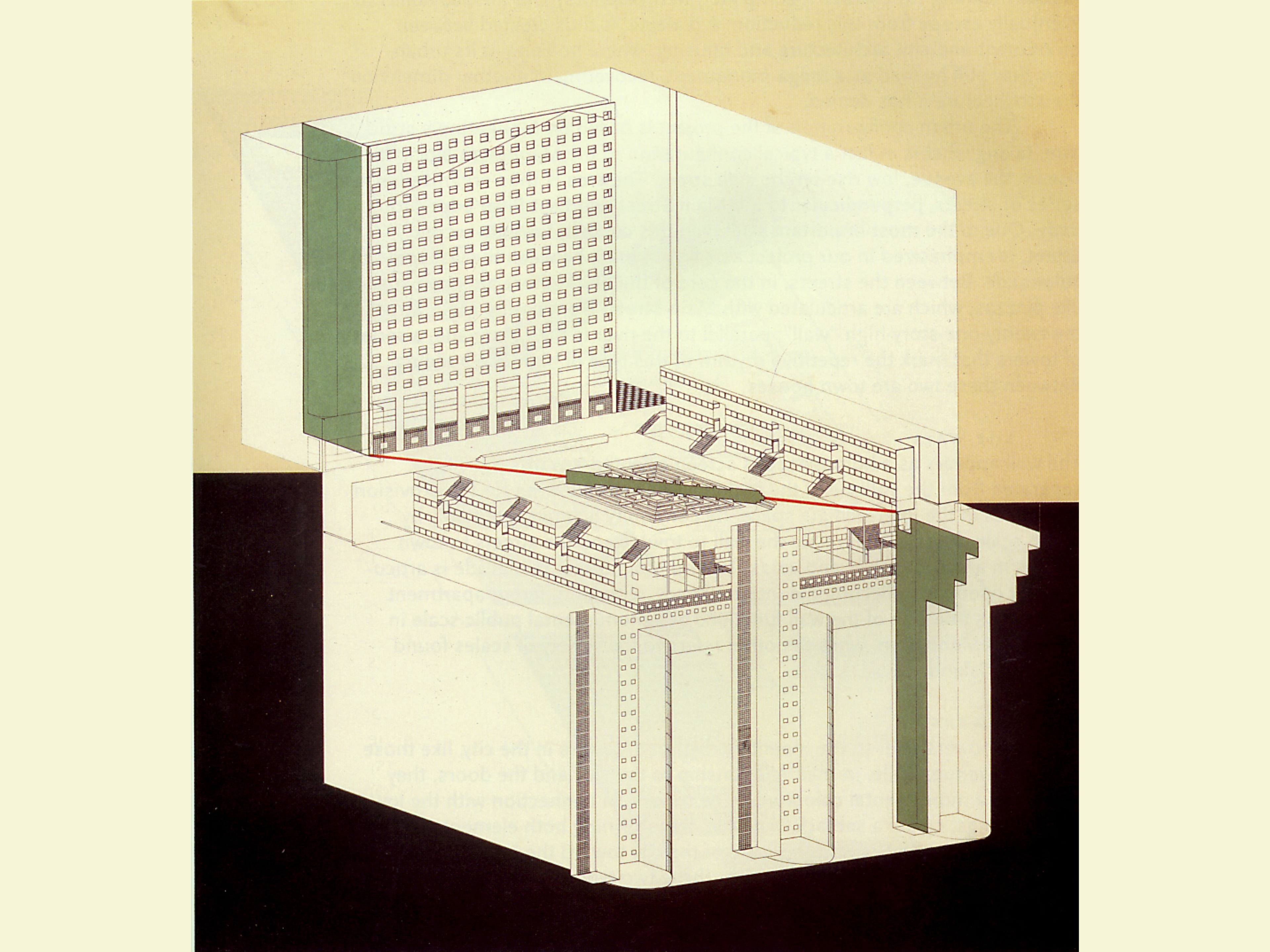

Transformation allows for the creation of elements that transform the original meaning. Examples of this process are apparent in the transformation of towers, such as those found on Sixth Avenue, into colonnades, of the high rise into a wall, and of the typical brownstone or town house into another type of low-rise housing, which is simultaneously transformed into terraced dwellings. These last, in conjunction with the towers in colonnade formation, produce the typical setback configuration of New York skyscrapers. We attempt here to pose the problem of the dissemination of meaning—of the production of meaning—as open signifying chainings. Our project attempts to organize a dispersion as a dialectic between the ideological tendency to reduce meaning (to enclose it completely in metaphors) and the possibility to eventually escape from this reduction. A dialectic is thus created between monument and city, architecture and housing, where housing in its urban logic may still be read as a mega-monument, recovering in another dimension the architecture it has denied.

(read more)

Wall & Towers

The wall appears as a homogeneous screen oriented towards the city, separated from the volume of the building and thus allowing for the provision of terraces in the intermediate space. Its continuity is interrupted only by urban scale doors, which relate the wall to towers and the streets to town houses in a play of solids and voids. Toward Main Street the facade is articulated by openings reflecting the interior space, with its different apartment types. Thus one side of the wall functions at a monumental public scale in relation to Manhattan, while the other refers to the variety of scales found inside the island.The glass towers refer to the repetitive rhythm of towers in the city, like those on Sixth Avenue, while, in their relationship to the wall and the doors, they appear as a monumental colonnade. The towers, in connection with the low-rise buildings, create a setback in profile, transforming both elements. While they function symbolically at the scale of the city toward the interior of the project, i.e., the courtyards and streets, these two types—towers and stepped housing—are a more complex and fragmented phenomenon. As seen from the wall, the towers relate to the urban landscape of the Manhattan skyline as accents between the ample vistas of the city. This effect is accentuated by the towers’ long, lit, glass shafts with small perforated windows, which play with the glittering lights of Manhattan across the river.

(read more)

Townhouses & Streets

The typical townhouse has been transformed. The stoop has become a public element that articulates public spaces through the building, connects streets with squares. The facades towards the streets or piazzas are treated in different manners, addressing the particular character of the space.The wall emphasizes the direction of Main Street and, at the same time, generates a parallel street. Between these two, in the depth of the wall, there are commercial and community facilities. The access to stores is on the side facing the low-rise buildings. Perpendicular to these, there are streets following the Manhattan grid.